An aging Billy Graham was once asked, “What was your greatest legacy as an evangelist?”

His answer: “Lausanne.”

The full title of Lausanne is the Lausanne Committee for World Evangelization, and the preconference reading was a document entitled The State of the Great Commission Report. Started by Billy Graham and John Stott, this congress has Western evangelical origins but truly transnational ambitions for the evangelical church worldwide. With over 5000 Christian leaders present from over 200 countries, this 50th anniversary gathering drew a rich variety of nationalities, traditions, and languages (even though everything was in English, with headsets for others). I gave some pre-congress thoughts in my last post.

I was truly overwhelmed by the experience, and although it was an emotionally charged week, I would say my overall impressions were quite positive. It was humbling to be among such dedicated Christians, many working in lonely, poor, or persecuted places on the planet. It was also tremendously enriching to meet so many diverse people from across the planet: we were all seated at tables in a giant auditorium and my table consisted of people from Uruguay, Malaysia, Norway, India, and the USA. In the hallways I took up conversations with people from such places as Nepal, Latvia, Belarus, Kenya, Malawi, UK, Kazakhstan, Israel, Denmark, China, and my favourite–the young theological student Daniel from The Gambia!

In fact, that there were some 100 delegates from China was a first for a Lausanne gathering since its beginning 50 years ago. I hope their voice was heard, even if their photographs were not taken.

It had all the trappings you can expect from an evangelical conference: enthusiastic singing, mostly of praise and worship songs coming from Western sources, although sometimes a verse would be sung in another language like Korean or Spanish; an emphasis on prayer, especially spontaneous prayers; a general egalitarianism, with few bishops present and more celebrities, like Rick Warren and the Getty family band; many reminiscences of the great revival moments around the world where conversions came in large numbers, and an emphasis on church planting. There were some dramatic comments from the front from time to time about “unreached people groups” and “every hour 4000 people perish in the darkness of hell,” but not as a rule.

Some things one may not have anticipated when the focus is on the Great Commission more than the Greatest Commandment or the Cultural Mandate: a constant reminder that God’s mission is both evangelism and social action, spiritual care and justice work. There were stirring presentations on subjects like climate change, social justice, sexual ethics, and a personal account given from the underworld of sex trafficking. There was little time given to discuss these arresting speeches, but they did remind all those present that the demands of love and care for others are pressing in on the church from many sides.

Furthermore, one of the strongest themes of the conference was collaboration, and we worked in groups focused on 25 “gaps” in the Great Commission. But many of these gaps have to do with social issues like AI, sexuality and gender, secularism, Islam, religious freedom, and holistic health (think of the plague of mental illness in the modern world). I was in a working group on “developing leaders of character”–brainstorming about ways to mitigate our scandal-ridden church. So the gathering had a wide focus of God’s mission in this deeply troubled topsy-turvey world.

A statement was released called the “Seoul Statement” (on Sept. 24th) elaborating on commitments to the Bible, the gospel, discipleship the church, but also with whole sections on personhood, human conflict, and technology. US Christian writer and leader Ed Stetzer accused the congress of “mission drift” from the evangelistic origins of Lausanne in his missives to North American attendees, but really this more holistic approach is part of the “integral mission” that Lausanne has embraced in its development over the decades since 1974. A speech on social justice from Ruth Padilla-DeBorst in the middle of the week ignited some protest and an email apology from Lausanne to all delegates. Lausanne, however, assigned her the topic of social justice and she gave testimony to its vital role in God’s mission–throughout the Bible and in our battle-scarred planet today.

Blood and Tears

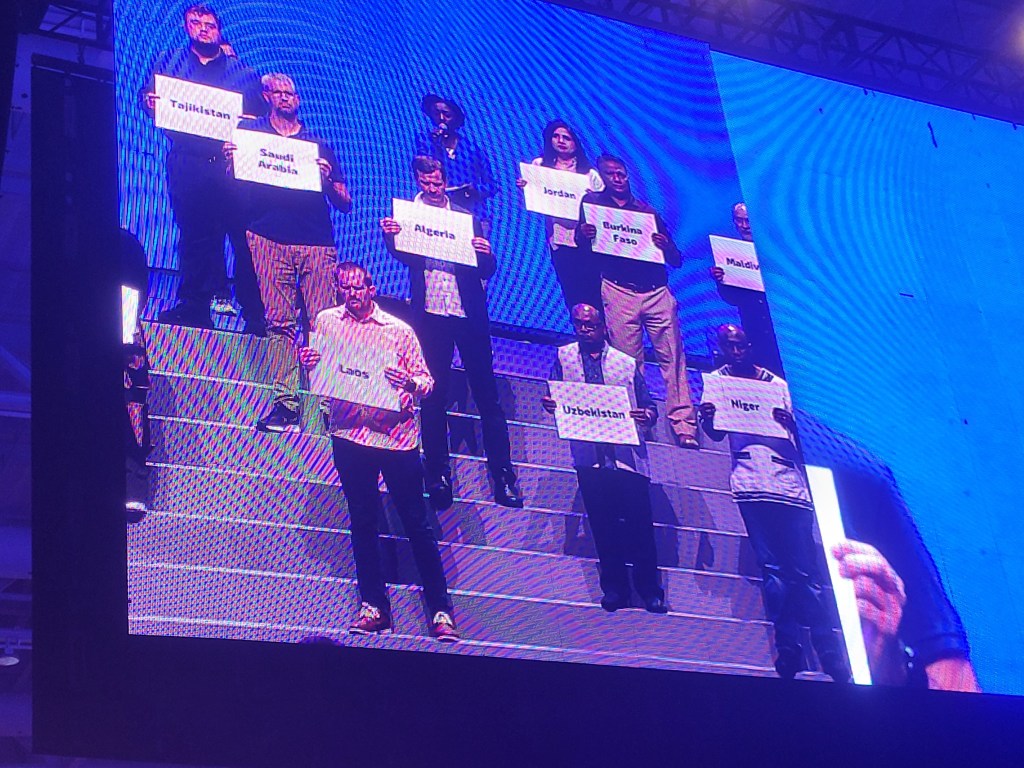

One day was dedicated to the persecuted church, and all participants were asked not to take any photos as people gave testimonies from China, sub-Saharan Africa, Iran, and India. Over 50 countries were named in a solemn ceremony that acknowledged Christians are persecuted, tortured and killed primarily for their faith in Jesus.

While Christians should be concerned about freedom of religion, conscience and speech for all people, I spoke with the Canadian director of Voice of the Martyrs, Floyd Brobbel, and he said that the persecution of Christians covers about 75 percent of religious persecution on the planet and about 90 percent of the martyrs are Christians. The majority of these are in sub-Saharan Africa.

There are also brothers and sisters suffering in war-torn and politically volatile countries. Intense speeches were made by Ukrainian, Palestinian, and Burundian Christian leaders. I spoke with a sister from Kenya, who said her current president was ruining her country and conniving to lengthen his term of office. A pastor from Belarus said the current leader had been in power for decades and allowed Russian President Putin to use his country as a buffer and storage zone for nuclear missiles. A young man from Latvia said he if he ever saw American soldiers silently exiting his country he would flee for Germany. They are poised for trouble.

He also said the two major issues in his country are fatherlessness and alcoholism. The woman from Kenya cited domestic abuse as a general expectation for marriage in her country. Many delegates from Africa and India sought to get my contact information, I suspect in many cases because they are hoping for some sponsorship from the West. “We need some lap top computers,” wrote one pastor to me through the congress directory app.

Looking backwards from my table across the auditorium.

Seeing the tremendous volatility of our world, I am grateful for the relative peace we have in Canada and recognize why the number of immigrants and international students is so high here. Our church in Canada struggles with “deconstructing faith” and consumer religion, something foreign to those in the desperate straits I’ve named here. “We in Canada just don’t know where the battle is anymore,” said the Voice of the Martyrs director to me. He’s probably right. We are awash in the clutter of our devices and their channels and screens. But how to keep this bigger perspective of the persecuted global church through the months and years of living in relatively free North America?

Hope in Technology?

“We must embrace and utilize the digital” said CEO of the Lausanne Movement Michael Oh. “It is not the answer, but a tool,” he added, emphasizing stewardship. He spoke of “intelligent recommendation engines” to help forward global mission. While the Seoul Statement seems a little less enthusiastic about technology, the congress overall gave the impression of technological endorsement.

A whole digital future display was set up in the convention centre with tech company displays and personnel filling the space to consult with congress delegates. One of the motivations named at the front was that the next generation are born and live within this digital world, so in order to reach them, we need to navigate the same space. This is my concern, however: are they “digital natives” or digital prisoners? If a people group is captive, is not the response to be emancipation? If they are living disembodied lives, is not the solution embodiment? We know the new devices affect everything from mental health to social isolation and even near sightedness–is this the extent of our missional imagination today, that technology becomes our medium of choice?

Technology, strategy, new hardware and software–these all have a place, but the current state of the planet requires adaptive, cultural changes, not so much technical innovation. In fact, any major change is first of all cultural, not technical.

Ironically, the conference wifi did not serve us well. Also ironic, the day this emphasis came up in the conference was the same day the New York Times carried an article entitled “When Computers Go Dark” where tech writer Steve Lohr writes: “New advances make our lives easier, but there are trade-offs. They can vanish quickly — in an outage, a hack or a pandemic. And as the economy has become more dependent on a smaller number of technology companies, we’ve become more susceptible to hiccups that affect them.”

I spoke with some theology graduate students from Fuller Seminary, California, over dinner who expressed concern over the sheer weight of the expense for so many of the congress frills: for the dozens of mega-banners, the special digital age exhibit, and the technological extravaganza of jumbotrons, dry ice, and dazzling array of spotlights and hi-fi speakers.

“I’m an Anabaptist Quaker,” one said, “and simplicity is a high value for us. This is the opposite.”

“The whole program has been over-scripted with an immensely tight schedule,” they added. “There hasn’t been room for discussion, spontaneity, or even networking.” For example, after the presentation on human sex trafficking, there was no time to talk at our tables. The program barreled on.

I asked someone if the last 2010 Lausanne conference in Cape Town was more relaxed. “More relaxed, yes,” they replied. “But also much more chaotic.” Conferences take on the character of their host culture, and we were in Korea, the capital of Samsung, LG, and Hyundai. I had taken the high-speed train from Busan to Seoul to visit a friend just before the conference. Korea is high-tech country, with all the perils and promise of such. Christian ministry, however, if it is to be incarnational, needs a critical posture towards the transhumanist future, and Lausanne 4 took serious note of this pretension in some specialized sub-gatherings I did not attend.

Typical Korea. Most people live in apartments.

Korean Church Drama

One special evening was dedicated to a fantastic dramatic presentation entitled the “12 Stones of the Korean Church.” Twelve key moments in the 140 year history of the Korean church were highlighted, included a spectacular revival in Pyongyang, North Korean in 1907. The story is told of missionaries and church leaders who hated each other, but who embraced and forgave each other, igniting the conversion of hundreds of people. Confession and revival were paired consistently, it seems. Other stories were quite tragic: Yu Gawn-sun, a 16-year old woman martyred for her resistance to the Japanese occupation in 1919; Moon Joon-kyung, a tremendously persistent female missionary to the southern islands, martyred by the North Koreans in 1950; and fragments of the gospels passed through North Korean jails in the 1990s, a time when the South Korean Church send food aid to the North and welcomed over 30,000 defectors across the volatile border.

The story was also told of Pastor Son Yang-won who worked with a leper community. Sadly, in the 1940s, as tensions with North Korea mounted, his two teenage sons were shot and killed by a left-wing youth. During the trial, which would have ended in the execution of the young man, Pastor Son pleaded for the boy’s life, saving him from an ugly verdict and actually adopted him as his own son. Sadly, Pastor Son was shot to death by North Korean soldiers in 1950, as he worked in his leper colony. He was buried beside his two sons.

One moment especially struck me, as it must have been embarrassing for the Koreans to even mention. During the Japanese occupation (1910-1945), thousands of missionaries were forced to evacuate from Korea, and the church was left to struggle under oppression. What was especially tragic was that the Japanese demanded that Christians bowed down to the Japanese emperor, who was considered a god to the Japanese.

Many Presbyterian leaders told their parishioners that they must obey the current governing authorities, and they capitulated to the Japanese by bowing down at local Shinto shrines. A smaller number resisted the edict, and paid for it with their freedom and their lives. After the Japanese occupation ended, there was much strife between those Christians who bowed down to the Japanese gods and those who did not, and much reconciliation had to be done.

This made me ask myself, what would the 12 stones of the Canadian church be and would it be any less dramatic? I think of the early missionaries and their hardships, the residential school scandal, church splits and the government funding of only one religious education system. A recent book by James Robertson entitled Overlooked: The Forgotten Origin Stories of Canadian Christianity might be one resource for such a history.

I had always thought of Korea as the missionary powerhouse of the planet of late, but reports are now that the next generation are exiting the church to a large degree–even in greater volumes than in North America. A Korean colleague says it is because there is little faith formation in the home, and parents are too busy working–at jobs and in the church. But the bigger picture is that Korea fertility rates are at 0.8 percent (!) which means the loss of the next generation is not just a church problem.

Evangelism and Ecumenism

Jacob is a retired pediatrician from Southern India, and he said it was good to be at Lausanne to meet people from around the world “struggling with the same issues of how to live in a multicultural society and still be a clear and authentic witness for Christ.”

Then he added, “But this should be more ecumenical. I’m surprised there are so many Pentecostals here but no Catholics.”

Indeed, the evangelicals who operate at the core of Lausanne actively court Pentecostal Christians, the fastest growing part of Christianity today. Some speakers emphasized this collaborative partnership and told some stories of getting together in mission. But Catholics, Orthodox, and mainline—which makes up over 80% of Christians today—are not officially part of the Lausanne endeavour.

One might argue that there is already enough difference to navigate when 200 countries are present, and so some doctrinal and spiritual affinity make sense. There may be other events that try to be more representative of the whole of Christianity—maybe the World Council of Churches comes closer, although it leans toward more mainline (liberal) denominations (it has 352 member churches). There the emphasis is different—less on evangelism and more on ecumenism, interfaith relations, and social justice. When the WCC met in Korea in 2013, conservative Korean churches protested it.

Workplace Ministry

One striking emphasis in the congress was on “workplace ministry”—both in presentations and in a workplace track that seemed to attract a significant proportion of those present. It was declared that 99 percent of Christians are not clergy or missionaries, and that their natural place to bear witness to their faith is the workplace. Many of the 25 “gaps” that were described assumed a Christian witness within broader culture.

A thoughtful commentary on the congress by Mission Lab writer Tyler Prieb makes some critical comments on this strategy. He suggests that 25 priorities is too many to focus the congress’ action, leaving things “messy” and with “a weak agenda for world leaders.” The “long list of priorities… feels more dilutive and less helpful than really clarifying a point of view on what is most critical right now.” Polycentric mission allows for geographical spread but he insists we still need a “conceptual centre” for where ministry should focus.

His critique turns to the assumed place of the church. If workplace or marketplace ministry is the future of mission, he says there is a “subtle sense that serious leaders don’t work for the church anymore” and the weight of mission shifts to the parachurch. The church is scattered but not gathered and “Christian-ish form of social entrepreneurship toward UN development goals” overshadows “kingdom distinctive.”

I think there is value in this critique, although it may overstate the case. It is also true that Lausanne favours the parachurch by its very structure and history, as opposed to the World Council of Churches, which is more church-focused. Moreover, speaking from Canada, the credibility of the church is severely weakened right now as my recent co-authored book shows. Maybe there is something intuitive in seeking a mission where the place of the church seems unclear. A transition is happening where instead of the church having a mission, our ministries are becoming the life of the church today.

Power Analysis

One recurring theme of the gathering was power. The first full day was a refrain focused on the power of the Holy Spirit. This was appropriate to the designated book of the bible for the week, which was Acts. “Do you leave room for the Holy Spirit in your ministry?” one of the first speakers asked attendees. It was noted that the year 2033 will be the 2000th anniversary of Pentecost. The first morning devotion emphasized “no mission without power” which I mistakenly heard as “know mission without power”–thinking of Jesus and his upside down kingdom of the cross.

There was also talk of “principalities and powers” – as we live in a world of contested territory–government powers, corporate powers, and military powers. I attended an “Anti-corruption and Integrity” workshop led by Canadian Willy Kotiuga. They spoke of corruption in the church, business, and government. Sadly, it was noted that the government of Kenya has put churches on the top of its corruption inspection list. Many churches have a bad reputation there. Willy spoke about advocacy, lobbying for accountability and transparency, and working with other organizations focused on anti-corruption.

Some mention was made of gendered, racial, and generational power, but power was most often associated with Western countries. The word “postcolonial” appeared a few times in the week, and the general notion of getting beyond the old missionary era was frequently addressed. The heart of the church now beats in the Global South (by the year 2050 it is estimated that four out of five Christians will live in the Global South). “Polycentric mission” was invoked, where there is no core geo-political location for the heart of Christianity (“from everywhere to anywhere”). There was a critique of the “ordered and cerebral” Western missions in contrast to the Holy Spirited experienced of African churches. In that line of thought, mention was made of the rapid spread of the Redeemed Church of God around the world, “made in heaven, assembled in Africa, and exported to the world.” The former margins are now coming to the former core of Christianity: “from the rest to the West.”

One of the speeches that seemed to resonate with many I spoke with was the presentation offered by Sarah Burel, a long-time Lausanne personality. She spoke of the importance of genuine repentance and travailing prayer for revival in the church. She charged the West not to equate mission with colonialism, and not to let cynicism or pessimism paralyze zeal. “Do not retreat,” she said. “God is not done with the European church yet. It is not dead, for we serve a God in the resurrection business.” Then she added, “The Global South cannot be independent of the West. We need a true partnership of North, South, East and West.” She then called for a global repentance movement—from corruption, abuse, and division and asked all delegates to get off their chairs and onto their knees.

It was said numerous times at the conference that the four most dangerous words in English were: “I don’t need you.” The general focus of the congress was on partnership rather than the antagonisms that come with postmodern power analysis.

On this note, there is no doubt that the American presence and leadership at Lausanne remains central. American delegates were by far the most numerous and most prominent on the stage. When we were asked to discuss at our tables what we need to confess in our local Christian circles, one Global South representative immediately said, “We struggle with negative feelings toward the American church. They have dominated too much of our Christian mission.” Then he added, “We are trying to recognize that we are brothers and sisters, and not ‘us’ and ‘them.’” A prerequisite to global mission is reconciliation. This was a constant theme, right up to the last moment on the last day when we did communion, led by two pastors: one Korean, one Japanese.

Future Lausannes will need to upstage more of the Global South.

A few people mentioned to me that the experience of gathering with 5000 Christian leaders from 200 countries across the planet could be spiritual transformative. “Have you been changed?” is the question.

Take Aways

So what am I gleaning out of this grand adventure on the other side the planet? This trip was at great cost to my charity organization and besides blogging on my experience, what comes out of such a rare and involved international gathering? Let me mention three things.

1. First of all, one of the key reasons I decided to ask my board’s permission for this trip is because a small group of university ministry leaders, lead by Global Scholars (USA) President Stan Wallace, were agitating for Lausanne to consider academic mission as one of its “issue networks.” These networks are sub-groups of Lausanne that use Lausanne’s brand and connections to develop transnational connections for collaboration around specific ministry goals. A bunch of us (including people from Intervarsity and IFES) met on Zoom for like a year before this event, planning to generate this new formal network.

We were rewarded with official status by Lausanne and were given a time and a room in which to gather any of the 5000 delegates who had interest in academic ministries. We called it the AMEN group–Academic Ministries and Educators Network. About 75 Christian leaders showed up for the meeting, and now we have a global WhatsApp, regular Zoom meetings scheduled, and a google drive for shared resources. We will see what comes out of this over months to come, but similar networking happened in all kinds of sub-topics at Lausanne, hopefully resulting in new partnerships and fresh initiatives in Christian mission around the world.

2. Secondly, I made many personal connections on the side — some planned, some part of the structure of the congress, and some rather spontaneous. One such relationship may become a new Canadian global scholar or even a board member. We will see.

3. Finally, this congress gave me a deeper sense of the English-speaking world of global evangelicalism. It has given me a fresh perspective. Most important in that regard is a new recognition of the shared experience of the malaise of secularism and church decline that is corroding the older established church around the world. I knew the Western church was waning, and our new book Blessed are the Undone has been a window into faith deconstruction in the modern world. What surprised me was that places like Uruguay and South Korea are also experiencing such secular push back and faith erosion. In a globalized world, modern disbelief can flow across borders as well as faith in Christ and his kingdom.

Which suggests a clearer sense of the task that lies ahead of the church in such contexts: how to partner together across the secularized milieu of our planet to dream in fresh ways of how the good news and its herald the church might offer a wired and weary culture some of the healing, help, and hope it so desperately needs. A balm that originates and flows from nothing less than God’s grace in Jesus Christ.

There were apparently something like 1000 Korean volunteers, helping out with everything from security, to directions, to getting you a taxi. They often stood in the hallways with signs and gave us the two-fingered heart symbol.

Thanks for this report and your insights.

LikeLike

Interesting report, appreciated the insight to the value of the conference.

LikeLike

Dear Peter, Thank you for all the work you put into this tremendous summary of the proceedings of the Lausanne 2024 gathering. I feel as if I have been a part of it. As you land and get into your routine again, do look ahead at a possible date for another lunch or coffee. Grace and Peace, Justin

LikeLike