“We Canadians make massive imports of culture unawares,” warned Calvin Seerveld. “I do not believe there is a sinister American plot to take over our nation,” he continued, but he wanted to stand on guard against any kitsch slinking in from the USA. This is what he said at a CBC radio conference in May 1990, but his words, like most of his writing, continue to ring with prophetic resonance today.

For me, he was a cherished preacher, writer, elder, and mentor, and these are my reflections on his life and writings on the occasion of his death. This piece was first published in Christian Courier (at about 1/7th the length!) I had intended to write something like this after an interview with him 3 years ago, but only now can I put some thoughts together. I offer a short bibliography at the end.

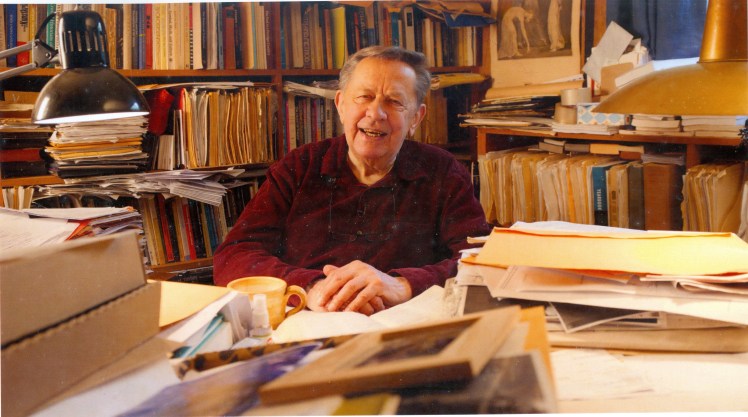

“My breathing patterns change daily,” he emailed me on July 24th this summer. “Often within a day. It has been bad.” He then fell asleep in the Lord on August 5th, 2025, four days before his 95th birthday. He was a professor of the philosophy of aesthetics at the Institute for Christian Studies in Toronto from 1972-1995, and never stopped writing until he died. He was a mentor of sorts to me, and I combed some of his writings to put this blog together as a way of giving thanks for his life and writing. For those curious about the core of his thought, Normative Aesthetics (2014) or the earlier Rainbows for a Fallen World (1980, 2005) would be a good place to start. This article’s title comes from the title of one of his last books–a commentary and translation of Ecclesiastes: God Picks Up the Pieces (2023).

His first breath was in 1930, on Long Island, New York. “I had good parents who were really Christian and wise,” he recalled. “Somehow they gave me biblical structure and room for myself to find the Way… I never had to rebel against my parents or the church into which I was born.” (BSWL 409) His Reformed church didn’t allow dancing, playing cards, or going to movies, but his parents were not legalistic about “worldly amusements.” He has many good memories from Long Island, including using cow patties for the bases in a neighbourhood game of baseball.

Identifying with the “Kleine Luyden“

He was never ashamed to say his father was a fish monger, and he worked alongside his father from age 10 to 22. The Seervelds ran the Great South Bay Fish Market on Long Island, a “clean, honest place where you can buy quality fish at a reasonable price with a smile, but there is a spirit in the store, a spirit of laughter, of fun, joy inside the buying and selling that strikes the observer pleasantly…” (INFOTL 242). He didn’t romanticize it, but neither did he turn up his nose to the fish. “I know God’s Grace can come down to a man’s hand and the flash of a scabby fish-knife…. The meanest work can be done to the Lord and is a holy service… an earthly hallelujah, priest service…” “That person has missed his or her calling whose daily work is not a thanksgiving to the Lord. (243)

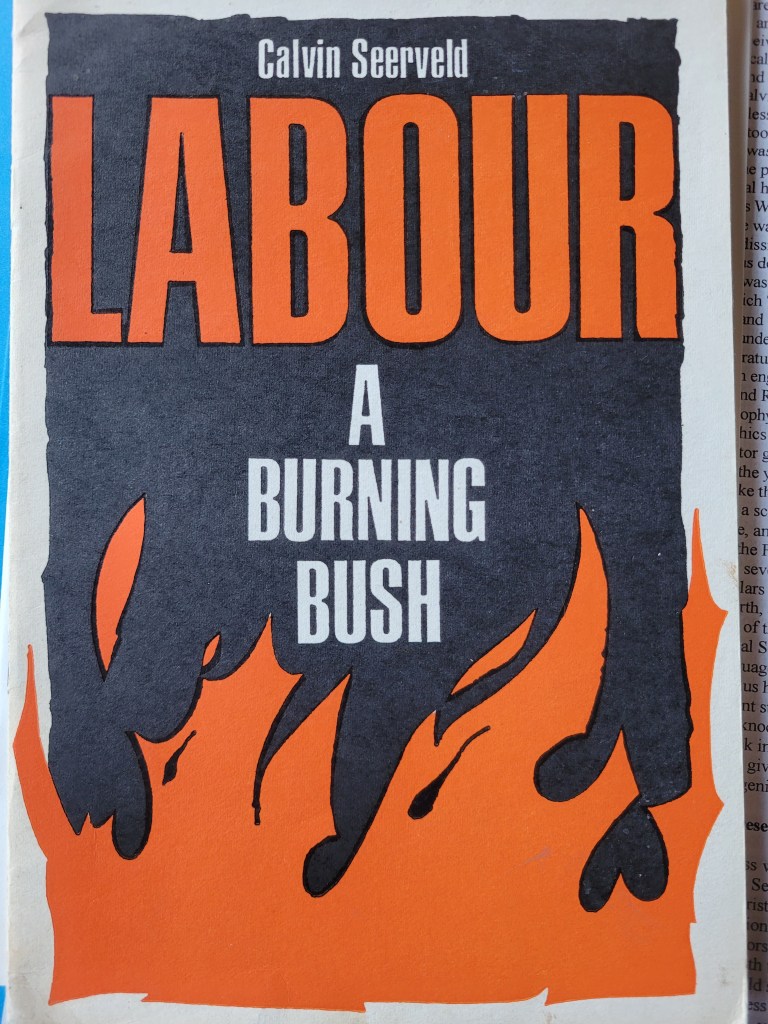

Seerveld would always identify with his working-class upbringing, and what Abraham Kuyper called “de kleine luyden”—literally “the little people” but better described as “ordinary folk” like the butcher, the baker, the candlestick maker; the non-elite or working class. In this way, Seerveld was passionate about all kingdom-of-God agencies, but he had a soft spot for the Christian Labour Association in Canada (CLAC). When speaking at a CLAC gathering of lumberjacks in Smithers BC—men who may not have understood his philosophical lingo but knew he was on their side against “ruthless secular antagonists.” He observed that “their rugged profiles and gnarled hands reminded me of every good thing I had learned intuitively from my Dad in the fish market, and you knew, in spite of our sin, God’s pillar of fire was present and visible that evening, as if Smithers…was the centre of God’s universe” (ITFOTL 35).

Seerveld could lose an audience with his expansive academic lexicon, but he didn’t look condescendingly on his audiences. “I do not make the mistake of thinking non-academic persons are uneducated,” he declared. “They may be street-educated, and incredibly savvy” (BFOL 187).

He did receive a superb education. In his public school years, he recalls learning piano (from his mom), then tuba, organ, and bass guitar. Then he took off in 1948 for four years to Calvin College in Michigan, years he describes as “priceless, and deeply formative intellectually.” He took a “usual overload” of seven courses plus audits (!), but he wasn’t colouring within all the lines there. One chapel he prepared was disallowed by staff mentors; an editorial he wrote for The Chimes was censored out (editor Nicholas Wolterstorff ran it as a blank space to make the point). He was also called into the President’s office for publicly dissing a major donor.

Still, he was deeply transformed through this education. “What changed my life” he writes, was the Vollenhoven idea channelled through Runner which “was the questioning of the synthesis of Greek and Christian thought” and the pursuit of “a biblically-grounded Christian philosophy that could frame action for literature, labour, and the laboratory.”

He broke an engagement with a young woman in his final year in Grand Rapids—after a long, intimate talk with a Calvin philosophy professor in John Ball Park. He agonized over the ethics of keeping and breaking promises, and this faculty mentor gave him permission to back out if he hadn’t slept with the young woman and doubted his love for her (28). So he broke the engagement.

He received a scholarship to University of Michigan in literature, and then received a Fulbright Scholarship to go to the Free University in Amsterdam. He would spend the next seven years in Europe, learning from some of the best scholars of the day, including Vollenhoven, Karl Barth, and Oscar Cullmann.

When I think of the meaning of the word “scholar,” I think of Cal Seerveld. A Fulbright Scholar, he knew at least five languages, wrote at least 21 books and composed 39 songs, plus hundreds of articles and essays. He lived in his basement study, sometimes never leaving for days. But when he knocked on Karl Barth’s door in Basel, Switzerland, back in the 1950s, to press him with some questions, he was given a jolt. He summarized the experience: “He was a genius and I wasn’t.”

Experiencing God’s Presence

I have never taken a class with Seerveld, but I have been a student of his in a sense. Seerveld was my designated ward elder at Willowdale Christian Reformed Church (Toronto) when I decided to do my profession of faith in May 1988, at age 19. We were in-between full-time pastors, so he led me through this rite of passage. I struggled with the reality of God’s presence—so, like Nicodemus, I would slip over to Seerveld’s house at night to test him. “I’m less interested in what you know about God, than whether you have actually encountered him,” I said. “Have you ever experienced God yourself?” He told me of a incident when he was hitchhiking in Italy and was picked up by some rough truck drivers. They seemed poised to sexually assault him, but when the truck stopped for a red light Seerveld jumped out of the vehicle. “I believe one of God’s angels saved my life that day,” he explained. In fact, Seerveld was a firm believer in angels, something he picked up from Karl Barth.

A second event came when he had an oral exam with famous theologian and ecumenist Oscar Cullmann, and so he spent two weeks locked up in a house translating the book of Romans from Greek to German. When he came to chapter 8 where Paul says we are saved from sin and evil only by faith in Jesus Christ and that his Spirit dwells in us causing us to cry “Daddy!” he suddenly sensed the Greek words were God himself in front on him. “Suddenly I became afraid of the book in my hand as if it throbbed with the very presence of the holy Lord God Almighty. It was like a burning bush that had just spoken directly to me. So I put the Bible on a chair, got down on my knees and prayed, shaken and awed by the power of what was written there” he recalls. “The sense that the Bible is my God talking to me live has never left me.” (BSWL 404 and 410).

He married Inès Cecile Naudin ten Cate (1956) and together they had three children, Anya, Gioia and Luke. He jokes that he and Inès “met in a snowdrift” because they met during a youth group ski trip. He explains that they had a “10-month honeymoon” in Rome, although at that time he also worked on his dissertation on Italian Benedetto Croce’s aesthetics. When he completed his PhD at the Free University (Amsterdam) in 1958 he went on to teach for a year at Belhaven College and from there to the fledgeling Trinity College, where he was the third choice as the philosophy professor. Alvin Plantinga turned the position down, and the runner up had a heart attack. But the Chicago years would prove to be extremely fruitful years for Seerveld, as students were inspired by his Reformational vision and he was able to help found the Patmos art gallery in town.

Now just what kind of a scholar was Seerveld? He was part of the wider Dutch-American Neo-Calvinist resurgence movement, jostling with the counter-culture of the 1960s with European philosophical frameworks. He was a “Reformational” philosopher and a professor of aesthetics in a Dooyeweerdian vein, with a penchant for rousing translations and commentaries of the Bible. He had a deep and penetrating focus on the doctrine of creation and saw the fabric of the world as ordered by the freedom-framing laws of God, with a complementary wariness for the human proclivity to twist and ruin what God declared good and very good. He was critical of the term “worldview,” considering it too cognitive, and preferred instead the more praxis-oriented language of a “committed world-and-life vision.”

What he said of his vocation, however, was more down-to-earth. “My art is rhetoric,” he wrote once. “I make speeches and song texts.” It was an apt summary of his vocation.

Like many Neo-Calvinists, he doesn’t fit neatly into evangelical or mainline categories. Like evangelicals, he shared a passion for the Bible and felt God speaking through the text. He loved the church, and believed a good Christian will engage culture, and in fact, make culture. Like many mainline theologians, his emphasis was always on the kingdom of God, the Spirit’s work within and beyond the church. Unlike many traditional Reformed folk, he was passionate about art and aesthetics.

While at Trinity, he saw four cultural options open for students of the day. The first three he was adamant to critique and avoid: a trust in science and its technologies, dropping out with the hippie cult of the day, or joining the political militants of the Radical Left. What was left was “the biblically centred life” that declares “We are not a rational machine, a sensitive plant, or a violent animal. We are creatures of the Creator, revealed in Jesus Christ, built to follow his norms for life and culture-making for the shalom of all.” This has been his life-long discerning task.

Concern for the Church

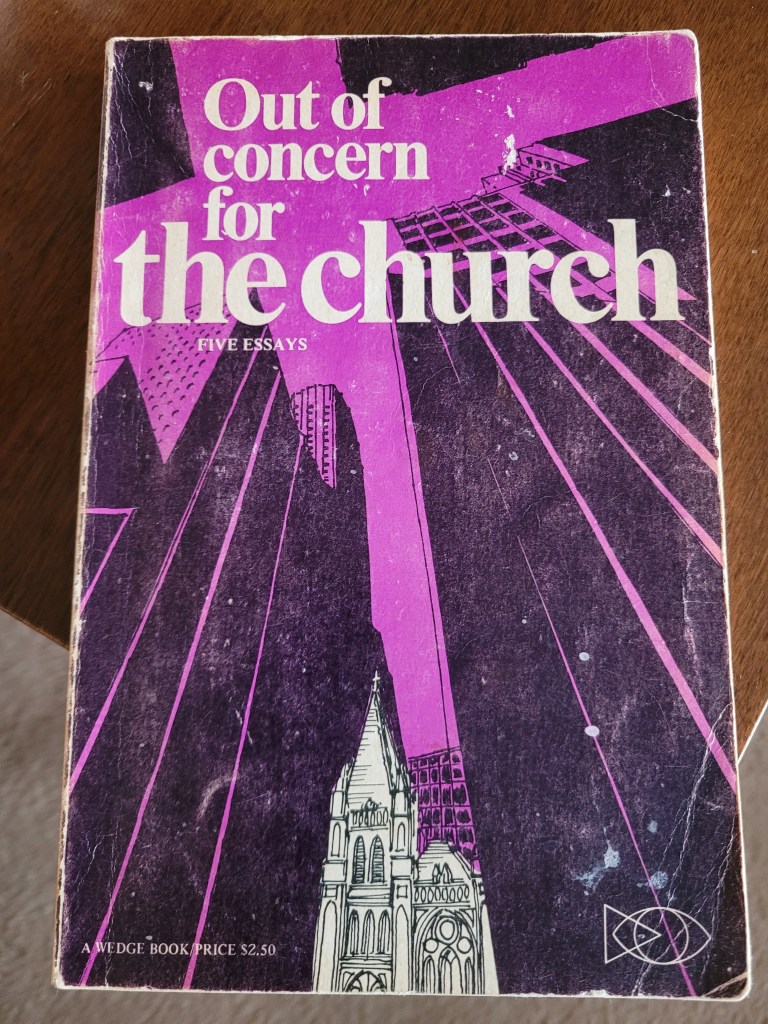

Just before leaving Trinity and shifting to the Institute for Christian Studies in Toronto, he was part of a critical book project called Out of Concern for the Church (1970), addressed to the Christian Reformed Church denomination. His contribution he entitled “A Modest Proposal for the Christian Reformed Church” but in the tradition of Jonathan Swift it was anything but mild. “Close Calvin Seminary,” was his proposal (the denominational seminary). “Disband all denominational boards and standing committees. Strip yourselves of ministerial status.”

It was a rhetorical move and it “caused a firestorm in the CRC.” But Seerveld was zealous against middle-class hypocrisy in the church, and he warned that the church was beginning to act more like a state.

“Whenever a church acts like a political entity it has lost its confessional savor,” he prophesied. It “feeds the bureaucratic creep… that leaves the manipulation of things to a few insiders…” and leads to the “establishmentarian petrifaction which sooner or later starts to settle in upon a church…”

Later in life Seerveld mellowed, and took a less preachy tone. In fact, in a short article he wrote for Geez magazine out of Winnipeg in 2008 he warns against counter-cultural strategies. Entitled “Better To Reform than Subvert, Also with Art” he critiques the “subversive” approach even as it “intends to upset what is in force.” Often in art, subversive approaches are “purposefully bizarre or violent, and usually out to mystify, shock, or antagonize the audience” and had “the feel of dishonest improvisation.” It has a “parasitic character” and to fight fire with fire “leaves only a scorched earth.”

This was some 38 years after his “Modest Proposal.” Was he speaking to his younger self? “Agreed, it is more fun to be a heretic than a religious stick-in-the-mud, but I am wary of the temptation to adopt the mantle of a latter-day, self-conscious prophet—‘Me and Jeremiah!’—because such a demeanour tends to overlook important fine differences and restrict alternatives in fundamentalist fashion, neglects the god-created good nature of institutional structures, and misses my own blind spots.” Better to be in Reformational testimony for the long haul, he insists, and cultivate a posture of being “wounded healers” (as Henri Nouwen suggested).

“Do good for Babylon, where some are exiled” he encourages readers, and “promote structural alternatives to the many perverse arrangements powerfully in place. It is a joyful task, even if the converted fail in a given generation. They do not have to succeed in producing a society of shalom. God will finally save the world.” Better to “find institutional openings to witness to the coming merciful just rule of Jesus Christ. Such a mentality is a scandal to the pragmatist and seems weak-kneed to those committed to be subversive. Geez.”

Seerveld actually mailed that article to me when I was researching a certain preacher who championed “the subversive spirituality of Jesus.” He insisted it was always better to be “thetical” than anti-thetical as a rule. He recalls that when he mused to Calvin philosophy professor Evan Runner that Dutch philosopher Herman Dooyeweerd was so “positive” as a scholar, Runner said to him: “You need to be biblically thetical before you can be critical.” Seerveld concluded years later: “That Vollenhoven wisdom has saved me over the years much grief.” (28)

That echoes something he had always practised: celebrating the kingdom value of institutions. He wrote in 2005 that “God’s firm covenantal grip… has provided society with various shelters… societal hugs.” These habitats or “societal hostels” he says are “set up by God for us humans to walk into, live in, maybe even serve as host for!” This includes the institutions of marriage, media, museums, medical clinics and markets—a whole rainbow of institutional structures in which the bulk of our lives take place, including the church. Seerveld was no anti-institutional radical, if the institutions acted as God’s embrace of his image-bearing pilgrims.

He participated regularly in his own home congregation in Willowdale, serving as elder but also preaching, teaching, praying, and leading in music and singing from the piano. He would sometimes offer his own fresh translations of Scripture and read them as part of the Sunday service. He would also write kind and encouraging emails to those who served in the church. He even wrote a sweet article for Christian Courier (February 2019) on one young fellow member of his congregation—a young Korean-Canadian woman named Danielle Im who ended up playing hockey for South Korea in the 2018 Olympic Games.

Seerveld spent years on a denominational Psalter Hymnal committee, discerning fresh psalms for God’s people to sing in church. Seerveld regards this endeavour as “some of the most important work he has done,” reported Craig Bartholomew. While Seerveld’s own songs are not as popular as Hillsong in many Christian Reformed Churches today, they are among the most poignant, and striking, in the hymnal. Consider the lines in his “Congregational Lament” where those in the pews sing “Why, Lord, must broken vows cut like a knife? How can one wedded body break in pieces? Could you not change the curse of this disaster?” (#576) Or his rendition of Song of Songs (#191) must be the only hymn with the words “erotic love” and “and “passion pure as blazing fire.”

Humourous Aesthetics

Seerveld loved the arts, but his approach to aesthetics was much broader. He saw aesthetics as the style with which we approach our whole lives. His contribution to the artistic character of life was a “doxological aesthetics” that placed all our creative endeavours before the face of God as a response to his good creaturely gifts.

So when I began playing with the idea of a PhD, I thought I would investigate the relationship between humour and religion, and so I took a summer course in 2008 with Dr. Adrienne Chaplin at ICS on “Art, Beauty and God: Recurring Themes in Theological Aesthetics.” My research proved that he was the perfect philosopher-friend for understanding the relation between humour and faith. He read some of my early writings in this area, and his notion of aesthetics as “allusivity” was key to my understanding of humour. We had lunch a few times during my PhD, and he gave me feedback on my sociological ruminations.

Most notions of art and aesthetics focus on an other-worldly beauty and harmony, but Seerveld’s take was much broader, and he elaborates on this in a popular way in Rainbows for a Fallen World (1980). Aesthetics is a nuancedness, a suggestiveness that helps people see things from a fresh angle. Art itself can be beautiful, but also potentially ugly, alarming, or funny. In fact, he consistently said that all art requires some sort of playful approach if it is to be imaginative. He writes that “to find something funny does take aesthetic awareness, I believe, a nuance-‘sensitivity,’ because the humourous while palpable is not exactly visible, it exists in the cracks of what’s there, so to speak” (NA 123). Art relies on “imaginativity.”

In his philosophy playfulness is a significant supportive moment in the aesthetic. He emphazies this aesthetic playfulness is not only a specific subject matter but a way of life, not just our approach to art, but our relationship with nature. “Walking down the street in a way that’s open to the reassuring winks that God is still up to his marvelous tricks, cajoling into wonder whoever has ears to hear and eyes to see nuances, wondering expectantly about the import of all these allusive features—such a walk is simply aesthetically wary” (RFFW 146). Seerveld never defines his aesthetic playfulness exactly, but he says we’ll know when it is missing from our life. It’s a readiness to fool around, an impulse to frolic and flair, a suppleness in one’s consciousness. Here the comic certainly can find its proper aesthetic place.

Seerveld goes so far as to say art that lacks a comic dimension is less than good art. Wary of any pretense, he names “the childish folly of us two-legged people trying so hard to walk by ourselves and falling flat on our faces with our lion-tired rationalizations and our exaggerated estimate of our strivings.” This hopeful, humble buoyancy should typify good art. “When art has lost the naïve sense of humour, fun, and sheer joy, there is little to protect it from becoming bizarre and barren” he concludes. This is not to say that everything needs a smile and a happily-ever-after ending, but that art that has lost a comic perspective of its own ambitions has become too self-important and professionalistic for its own good (ITFOTL 355-359). In sum, aesthetics not only includes a comic dimension, it requires it.

My views on religion, play, charisma, and comedy are more fully expanded upon in a chapter in my book The Subversive Evangelical (McGill-Queen’s 2019)–specifically the chapter entitled “The ‘Irreligious’ Paradox: The Playful Production of Ironic Evangelicalism.” What comes after that book, sadly, taps more into Seerveld’s focus on lament–see my Blessed are the Undone (New Leaf 2024). This work interviews those “deconstructed” by such things as the megachurch scandals that reveal clergy sexual abuse. More on lament below.

The ICS Years

Seerveld served as a senior member at the Institute for Christian Studies from 1972-1995. I imagine him as a passionate and mesmerizing lecturer, and a pastoral mentor. Yet he jokes that his first class of students, eager to learn about the philosophy of aesthetics, mostly dropped the course before he even hit his stride in the semester. He suspects he gave them too much Immanuel Kant, and not enough Jesus. It was the days of the Jesus People, after all. Still, he has named some of his former students as current friends and collaborators, which was one of the joys of his career.

He describes the ICS as “a kind of L’Abri centre for brilliant misfits fleeing the secular university system and the anti-intellectual evangelical church backgrounds”… “a genuine concrete community of sinful saints trying to put creatural ordinances into practise under the searchlight of Holy Scripture in obedience to the Rule of Jesus Christ on earth in history.” As a small urban ghetto of young professors from different disciplines, all used to having their utterances scribbled down by impressionable students, ICS could be an intense community. One day colleagues might “knock your block off” but on another day one might “give you all the shirts off his back … and walk with you ten miles of sorrow, not just two.” It was a season of “prayer, tears and hugs that would have even made Promise Keepers jealous” (33).

In 2009 David Schwartz wrote a short history of “the New Left and Radical Evangelicalism” in the 1960s and he says that “some evangelicals willingly drew resources and inspiration from the New Left.” He explains that they were reacting to much of what was happening in the USA: “galvanized by a continued racial caste system in the South, by growing military action in Southeast Asia, and by disillusionment with America and its technocracy,” they “denounced the evangelical establishment for its inaction against structural injustice.” He describes these radical evangelicals “liberal use of apocalyptic language” and cites Seerveld, who wrote about “an apocalyptic sureness that a Judgment Day is coming to help the Oppressed.” (Seerveld, “Christian Faith for Today,” Vanguard (January–February 1972): 9). Seerveld was never hesitant to invoke spiritual forces and events mentioned in the Bible and, as G. M. Birtwhistle (in a review of Fresh Olive Leaves) says appreciatively about Seerveld: he “fuses real Christianity with the socialist tradition in writing about the poor” (95).

Tymen E. Hofman in The Canadian Story of the CRC says the “Young Turks” at ICS “caused a firestorm in the CRC” and this got ICS “into a lot of hot water” but they “learned some good lessons along the way” (100). Bob Vandervennen in his history of ICS describes the turbulence caused when an academic triumphalism and embrace of counter-culture engages with a constituency of insecure and feisty Dutch immigrants. It is telling, however, that the chapter entitled “the Rough Road of Controversy” doesn’t mention Seerveld at all. He could be arresting in his language, but I can’t see him being deliberately divisive. I wasn’t there, so I can’t speak too definitively about the younger Cal Seerveld.

Still, I know Seerveld did cause some controversy (even beyond his “modest proposal”). He gave provocative lectures on nudity and nakedness, including a talk entitled: “The Christian Case for Free Love” (1973). But in the questions period after he concedes there are things he’s not sure of (the recording is available on the Calvin Digital Commons). Later in life, he seems a little apologetic about his earlier years in a speech he gave upon his receiving the distinguished alumni award at Calvin University in 1996. He says, “No matter my own sin or any evil directed my way, God has always marvellously turned it to good” (36).

To Hell and Back

Was Seerveld a conservative or a liberal? I don’t think he fit neatly into any stereotyped categories. He was idiosyncratic, genuinely “Seerveldian.” He was conversant with the art world, often the centre of the counter-culture; and yet he spent much of his time translating Scripture and preaching in conservative Dutch-Canadian churches. I don’t think he was entirely predictable in his response to social issues. Like Walt Whitman, whom he quoted me once, although in reference to someone else, I think it could apply in ways to Seerveld: “Do I contradict myself? Very well, then I contradict myself, I am large, I contain multitudes” (Songs to Myself).

My evening conversations with Seerveld at his home included a theological topic that deeply troubled me: the notion of Hell as a place of eternal torment for all the people who aren’t cognitively assenting as committed Christians. I lived in Toronto, among millions of neighbours who were not coming to church. My adolescent heart pondered these things deeply: were they all doomed? Surely this is not just. We talked at length about this. In the end, we agreed it wasn’t any of my business who was going where and why. I should just know for myself where I belong and by whom I am called.

So in very pastoral fashion, he chose my profession of faith verse as Isaiah 43:1:

But now, this is what the Lord says

—he who created you, O Jacob

he who formed you, O Israel:

“Fear not, for I have redeemed you;

I have summoned you by name;

you are mine.”

It was his way of saying to me: don’t be overly concerned about the secret things of God (Deut. 29:29). God is the Judge, and he works justice and righteous for the nations, and he gracious and compassionate, slow to anger and abounding in steadfast love. Know that you are his, and rest in that assurance.

Kitsch and Lament

Seerveld could be pastoral, but he wasn’t afraid to knock over sacred cows. He had startling words against kitsch, those trinkets and ornaments which the kleine luyden often treasure. He couldn’t stomach it: “is so hurtful, if not evil… fake and inferior… it accepts the technocratic denaturing of ordinary life… nostalgically. Willing to be slick, it always glitters somehow, bewitching the simple with illusions of grandeur… it is emotionally cheap… never enlarges experience; it blandly affects a show to stimulate feelings of exquisiteness or a mood of supernal tenderness, but it flops into bathos simply because it is ersatz…” (RFFW 63). He might have been more gentle about it in his later years, but paraphrasing another professor, he said kitsch “canonizes immaturity… thrives on sentimentality… wallows in self-congratulatory longings, superficially fulfilled, and therefore encourages one to be babyish.” In short, kitsch is “art devoid of the possibility of shit” (quote from Milan Kundera). The four-letter word was probably acceptable in Dutch-Canadian contexts, but it might break trust with any more evangelical Christians.

Yet when I went to Seerveld’s house to interview him a few years ago, I noticed a colourful and almost comical porcelain hen prominently displayed on the piano. I inquired about it, as it seemed out of place. “It was a gift I gave my mother as a boy,” is what I recall he said. But that would seem sentimental, and unSeerveldian. I also notice he recommended reading Peanuts and had this cartoon on his wall of Snoopy and Charlie Brown. Charlie Brown says, “Snoopy, some day we will all die.” Snoopy replies: “True, but on all other days, we will not.” Perhaps he saw it as a sort of proverb, a note from Lady Wisdom.

Part of his aversion to kitsch relates to his endorsement of lament, which is a normative response to the pain of the world. Kitsch denies tragedy. They say up to one third of the Psalms are lament Psalms, and Seerveld saw Western Christianity and its Praise and Worship wares as avoiding this deeply human need to cry out to God in grief. Like the theology of the prosperity gospel, we champion the “abundant life in Christ” while overlooking “take up your cross and follow me.” Seerveld’s creation theology would never let the effect of sin cloud out the “it is good” of creation, but neither did he go light on the ever-present darkness that lingers yet as we await the coming of the King.

About a year before my profession of faith in 1988, my body was crushed in a brutal car accident. I was broken in so many places I had to be whisked to the Sunnybrook Trauma Centre in Toronto, where I was reconstructed over the span of almost two months. I still have 11 metal plates with screws scattered across the front of my skull. Because we had no pastor at that time, Seerveld was asked to come and visit me. His comfort zone was the lecture hall, not the trauma unit, but he tentatively ventured in and offered his prayers, for which I am deeply grateful. “Why, Lord, must any child of yours be hurt?” he wrote in the grey Psalter #576. “Does all our pain and sorrow somehow please you?” He says in a short article entitled “Pain is a Four-Letter Word” (2001) that this song arose out of his experiences as an elder at Willowdale.

This lament song is anything but upbeat, and there are no guitar chords given. This “mournful melody” has Genevan Psalter roots and grit, and “is wedded to crises and to facing inexplicable evil in faith.” Lament should be part of every congregations repertoire, “weaning them from the comfortable tunes and choruses” and enabling them to “sing the tough stuff.” There was something muscular in Seerveld’s theology that wasn’t tapping into readily available machismo; it had grit and an unwavering persistance grounded in covenantal faith.

One of the art pieces that appears over and over in his oeuvre is Ossip Zadkine’s “De verwoeste stad” (“The Destroyed City”), a giant bronze statue in Rotterdam harbour, unveiled in 1953. Commemorating the bombing of Rotterdam in May 1940 by Hitler’s henchmen, Seerveld writes that its no somber obelisk. “He presents a broken torso with a gaping hole, writhing on massive legs, with huge lumbering arms raised like those of a Moses pleading in protest to God in the skies from which the devastation came. It reminds survivors and may even stir the naïve to imagine the crushing, tortured, wasted humanity which modern technocratic war both conceals and metes out.” (“Both More and Less Than a Matter of Taste” 1993, p, 11). Like all those who lament horrific waste, its heart was gutted while it pleads “deliver us from evil” (OBH 43). Seerveld was drawn to this kind of emotional honesty in his sermons and in art.

Reading God’s Word like a Child

In the last 10 years I went to visit him a few times, including once with my son, Joseph. He fed us lunch, and we spoke about my writings, his caring for Inès, and life in Willowdale. He gave me a number of his newer books, and I reviewed his book on Proverbs for Christian Courier. He asked me to review his book on Ecclesiastes, which I have quoted innumerable times, but unfortunately never completed a review.

In his later years he paid particular attention to friendship, and in one mailing to me of his article “The Gift of Friendship” he wrote in his characteristic ink pen, “On the way to friendship, Cal.” In this essay he reviews the Greek, Roman, and Chinese notions of friendship and offers his own definition: “Friendship is a close and informal relation of mutual trust and intimacy enjoyed by a couple of humans who have consensual respect bracketed with affection and an affinity for one another that lasts a while.” He then tells a few stories of his friends over the decades, including Dewey Hoitinga, who he was friends with ever since Calvin, except for a philosophical falling out between them that lasted ten years. Nice to know they renewed their affection for each other later. Redemption happens.

Cal also told me about his regular meetings with Jane Hengeveld after Inès died. She would come over with some homemade soup (and I know from experience she makes great cakes, too) and in exchange, Cal would open the Scriptures to her, reading in his characteristically arresting way, yet with the trust of a child.

The Scriptures were extremely precious to Cal, and he was adamant about how skillfully believers ought to read it. He offered short training sessions on reading Scripture at Willowdale CRC, and he wrote “How to Read the Bible Like a Grown-up Child” for The Banner in 1995. He says reading the bible regularly, and with a friend, can be fun, intriguing, and “we felt we could just take hold of God and pull for blessings.”

The Bible is not a book to prove your point or solve your personal problems. It is the “true account of how God works and what God wants done on earth.” “You have to give up your own agenda” he urged; “you have to dwell in the text” and yet also “become acquainted with the whole woven tapestry of the Bible from Genesis to Revelation.” “The Bible is not a fast read,” like short TODAY readings suggest. “You cannot read the Bible rightly if you are in a hurry.” This may cause hesitation on those reading a One-Year Bible: don’t read just to get through it!

He shunned the casual read, and certainly did not see Scripture as an encounter with some chum—or a philosophical opponent. “Reading the Bible argumentatively also ruins the fun and scariness of hearing God’s voice, which can caress your cheek lightly or suddenly hit you in the solar plexus.” (405). Seerveld urges believers to memorize Scripture, explaining how God’s Word can come to you in times of trouble. He tells the story of being thrown into the water by a swimming instructor in 1939 and nearly drowning and thinking of Psalm 146:3 as he went down the third time. “Don’t join yourself trustfully with tyrannical lords: in humans there is no salvation at all” (Seerveld’s translation).

“It is an error to reduce the Bible to recipes for one’s needs,” he insisted (406). “It is not the mother of all self-help books. And it was not written, I believe, to make us feel good.” Yet “once you catch the spoken-word character of the Bible, God’s Word is a re-hot goad and a tender hug. The point is to actually hear God’s voice—not just the scripted words—and meet the Lord’s ongoing, connected, and promising deeds happening now.” Try some commentaries, he said. “Let your imagination follow the text as a grow-up secure in someone’s love. And so you become a wide-eyed child again, hanging on to God’s words, so full of surprises for sinners” (407).

Seerveldian Style

Seerveld’s writing and speaking was often a romp with aesthetics, philosophy, and Scripture—he was a true Reformational interdisciplinarian. When he lectured or preached his words could bite, cut, and spark, with multiple adjectives and long clauses that stretched out his breath. Bob Vandervennen said this was “exuberant flair” and his student Lambert Zuidervaart described his speaking as taking a consistent “hortatory” (persuasive) tone. You would have to try hard to fall asleep, as the words sometimes came as a torrent, catching you unawares, juxtaposing ancient and modern in a phrase.

Cal could be relentless. Like an AA confessional, he lectured: “Hi, my name is Cal. I’m a workaholic. I feel good when I put in a solid 15-hour day. I love the work at my desk reading books, imagining, thinking things through, and trying to write down discoveries and insights.” He would pull some all-nighters and said “at a certain point the endorphins would kick in, you got a high, the writer’s block would break, and it would be exhilarating!” (NA 111).

Lambert Zuidervaart surprisingly summarizes Seerveld’s aesthetic: “Calvin Seerveld has not worried about being fashionable” (iNA p. xiii). He had many idiosyncrasies, including keeping his telephone number unlisted. Sometimes he would send me a little letter with an article he had written. The envelopes were always a collage of colourful stamps, including 2 cent stamps. They were not dutifully confined to the corner of the envelope either, and I suspect many were re-used.

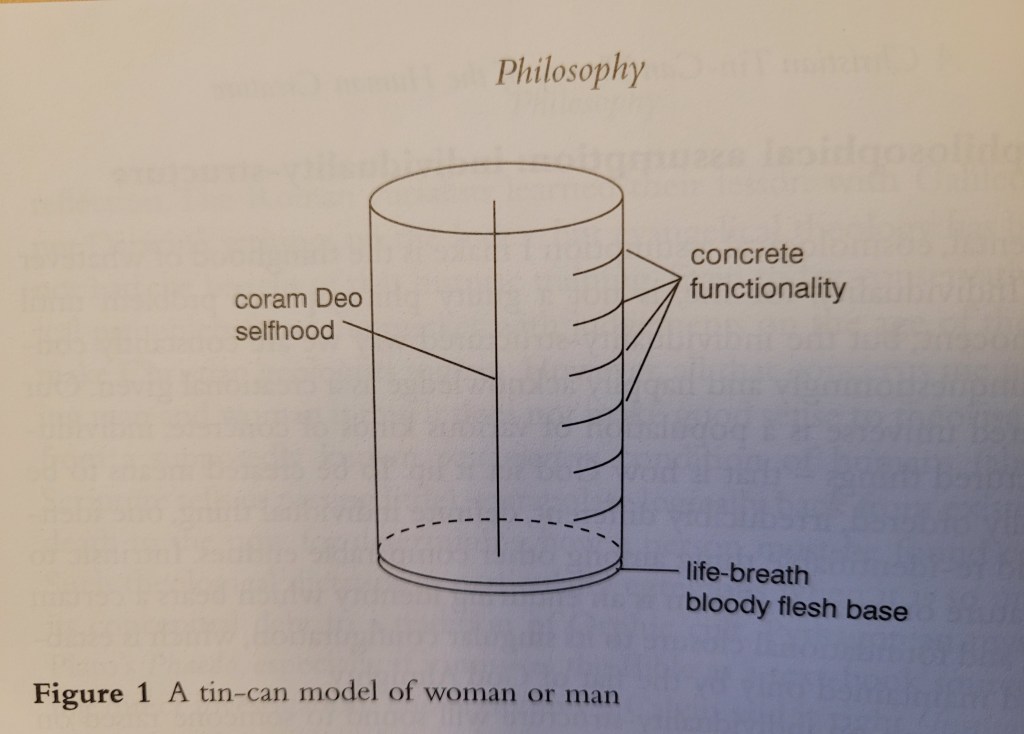

He wasn’t a flamboyant artist drawing attention to himself through his clothes, yet everything he did seemed to be intentional. He could preach with a scarf, or often in his corduroy suit jacket with its leather patches on the elbows. He chose the image of a tin-can to describe what he subsequently called his “tin-can theory of human nature.” He chose this image, he explained, “to nip in the bud any Humanistic pride in our responsible grandeur in creation” (113).

Regardless of the style, the content was arresting, convicting, and jostled you. He spoke like he really believed the Scriptures were the Covenanting LORD God Almighty Speaking To Us; he took God’s laws seriously, and talked about angels, demons, and Judgement Day like they were not fables but imminent realities that were larger than our casual approach was ready to receive. Yet his style was gripping and impressive, in the best sense. Gideon Strauss says the book Rainbows for a Fallen World and the article “Footprints in the Snow” (an essay on tradition) by Seerveld “are the most important things I have read, outside of the Bible itself” (CEHW xiii).

He could also be quite scatological, and not just in his critique of kitsch. Drawing on the language of Ezekiel, he spoke of sin as our “pellets of dung” and “our abominable lukewarm crap”—a kind of “ontological masturbation” (ITFOTL 55). In his commentary on Ecclesiastes’ theme of “meaninglessness” or “vanity” he explains that the Hebrew term can mean “a whiff of (bad) air” or “flatulence.” It is the same term used to refer to idols, which are like “passing gas” or “a fart” or “Big Stink”—in a phrase “’The Most Enormous Puff Possible of Stinking Hot Air,’ condemnably so!” (9) He even says when speaking of human nature that “good creaturely realities like praying, sleeping, eating, thinking, defecating, are God’s gifts we may receive with thanksgiving” (NA 121). I imagine he received some pleasure in rattling middle-class sensibilities, even if he also received in return some perturbed listener remarks.

Seerveld was asked about the endless hours he spent holed up in “monastic solitude in the basement study.” “Study is life too,” he argued back. “Ideas can kill people, or make them alive… The whole world of cultured history with all its sin, vanity, lust, and waste pass before me in my study… Does anyone these days pray for scholars living and dying in their studies?” (BSWL 411) Good question. I know one campus minister who prayed for the research of professors at his university. Not a bad idea.

Parting Ways

In December 2024 he wrote a letter to Classis Toronto, where his licence to exhort resides. “Because of the recent Synodical decision on sexuality, as I understand what has happened (2022-2024), demanding that any leadership in the CRCNA must believe that homophilic unions entail flagrant unrepentant sin, I believe I need to return my permission to exhort in the CRCNA which now stands for such a judgment.” So he sends this letter with “sorrowful conviction that Synod has over-reached its authority and now has declared the CRCNA communion stands officially for something that has wrongly singled out, judged and hurt many fellow believers of Jesus Christ, like me.” This is not the CRC communion that he had nurtured through the decades, and he wanted to declare his distance from it.

In March 2025 he signed a letter to Zach King written by John and Bev Banstra, a letter that passionately argued King’s “pastoral letter re US/Canada relationships (February 26, 2025) fell far short of the mark. It was tepid and missed the gravity of the threats that Canada and Canadian members of the CRC are experiencing.” Not needing to be the spotlight himself, Seerveld was generous with support for others with whom he felt common cause.

After a number of years with Alzheimers, in November 2021, his dear wife Inès went to sleep. At her Memorial and Celebrative Service he said a few words, including a small confession: “Perfectionist me over-worked, and only later realized the family burden Inès had cheerfully, as if normal, and meaningfully absorbed…. Without her as wife I would have perished long ago, since I am a worrier, and Inès had the reserve of aplomb… I have deep admiration for her resilience, and love for her as the woman I owe my life to.” They had come very far together, in time and geography.

Death, Be Not Proud

Cal often spoke of death as “sleep.” He sent me a Memento Mori service he prepared for his Willowdale congregation in June 2021 during COVID. It was intended as a “memorial service and celebration for loved ones who have left us.” There he translates the scream of Psalm 77 and says the whole congregation should grieve along with those who have lost loved ones. “The disappearance of a close friend also hurts like losing part of yourself” and so like the Psalmist, grieving is normal and right. “Godly grieving,” however, is “an empathy that gently stirs up hope in those gripped by sorrow… [which] slowly turns regret into a restored opening of expectation that the LORD God has something surprising in mind for you, you may anticipate… given time believers’ griefs are softened, modified, overcome by the reality of the resurrection!”

Then he says, “My confession is this: I believe the Scriptures proclaim that I, as a sinful saved child of God will not die (John 6:41-51).” He quotes Jesus as saying he is the power of resurrected life and that Paul and Jesus both spoke of believers’ death as “sleep.” “Much of what happens after one ‘gives up the ghost’ (the breath of life) remains a mystery, but the reality of ‘life everlasting’ for those who believe the historical Jesus Christ was the son of almighty God on earth, is certain.”

Always wary of sentimentality, he says to his friends: “So let me dare say: Do not be sad or lament when I have gone to sleep, people, even if you should miss me, because I will ‘be at home with the Lord’ (II Cor 5:5-8).” He adds: “I have long believed this preposterous proclamation of God’s Word.” It echoes an article he wrote for Christianity Today in March 31, 1958 (p. 11-13), entitled “Gone with the Resurrection!”—a reference to the end of death itself (and shortly after the debut of the blockbuster film Gone with the Wind). There he writes: “Not life after death” but “life or death”; “and if you believe on the Lord Jesus Christ you will not die but live!”

He gives instructions to those left behind at the day of his death. “I know I cannot die. When I shall go to sleep I will not want those who are still awake to cry, to mourn my sleeping—because I am alive, not dead!” Jesus said, “Let the dead bury the dead.” He ends the article: “To know that death really is make-believe, and to behave accordingly: this is the gracious wisdom of a child, a child in the Kingdom of the Resurrected Lord” (13).

He explained on a few occasions that he looked forward to the new earth. “Work in my father’s fish store, reading books over the years as a student, preparing breakfast as a parent, and thinking hard long hours in the study has usually been leisural, not hurried, except for the curse of deadlines. Thank God, on the new earth there will be no deadlines for anybody—imagine!” (121)

How to sum up Seerveld’s contribution to church, art, education, and God’s whole multifaceted kingdom society? Craig Bartholomew ends his introduction to Seerveld with this summary: “The passion of Seerveld’s life has been to serve up bread, and not stones to his neighbours in his life and scholarship.” (INTFOTL 21, Trinity Homecoming). Nicholas Wolterstorff looks back with Cal in a letter at the beginning of Seerveld’s festschrift—called Pledges of Jubilee: he reflects on what they learned together “back there in those magical student days: We learned that the work of the Christian academic can be a form of diakonia to the people of God, and to humanity in general… to the human flourishing which faithful learning serves” (xiv).

I will end with Cal’s own words, words he spoke as he received the distinguished alumni award at Calvin University in May 1996. As the spring evening waned he felt “the angels smiling along in heaven tonight” because angels “like it when God’s mixed-up people come through tough times and temptations to go it alone, and then are surprised, as sinful saints, by the joy to be found in celebrating one another’s gifts in play for the Lord this side of the grave.”

He ends his autobiographical comments with a blessing for the People of God gathered there. He probably raised his hands out of his corduroy suit jacket as he exhorted them: “May God bless you… with the communal vision and stamina to be scrupulously, joyfully faithful in your thetical and critical educative task, resolute, open-handed, historically sensitive, and restoratively busy in our Lord’s amazing, prodigal world” (37).

No doubt he would want to add: though we live in a “world of lies” where people try to “live by the dollar alone”—a time that could be described as “in the twilight of Western thought, in the throes of something big going to pieces”—we can know, in godly Old Testamented wisdom, that “God picks up the pieces.”

A Short Bibliography

Birtwistle, G. M. (2003). Calvin Seerveld, Bearing Fresh Olive Leaves. Alternative Steps in Understanding Art. Philosophia Reformata, 68(1), 93–95. https://doi.org/10.1163/22116117-90000280

Cuthill, C. (2025). Cal Seerveld’s Rich Legacy. Christian Courier. https://www.christiancourier.ca/cal-seervelds-rich-legacy/

Griffioen, S. (2025). In Memoriam Calvin Seerveld (1930–2025). Philosophia Reformata, 1, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1163/23528230-bja10123

Guesch, C. (2025). Vintage Seerveld. https://www.christiancourier.ca/vintage-seerveld/

Huyser-Honig, S., & Huyser-Honig, J. (2008). Bringing Our Pain to God: Michael Card and Calvin Seerveld on biblical lament in worship. Calvin Institute of Christian Worship. https://worship.calvin.edu/resources/articles/bringing-our-pain-god-michael-card-and-calvin-seerveld-biblical-lament-worship

Jacobs, N. (2009). How Should Christians Be Stewards of Art? A Response to Calvin Seerveld. Journal of Markets and Morality, 12(2), 387–392.

Lauterio, R. (2025, August 12). Thank You Lord Jesus for Calvin G. Seerveld (1930–2025)—Cántaro Institute. https://cantaroinstitute.org/thank-you-lord-jesus-for-calvin-g-seerveld-1930-2025/

Lugt, W. V. (2025, August 6). On Calvin Seerveld and Pioneers in Theology and the Arts [Substack newsletter]. One Astonishing Thing After Another. https://wesleyvanderlugt.substack.com/p/on-calvin-seerveld-and-pioneers-in

Pott, J. (2025, September 29). Remembering My Great Teacher Calvin Seerveld. Reformed Journal. https://reformedjournal.com/2025/09/29/remembering-my-great-teacher-calvin-seerveld/

Seerveld, C. (1967). The Greatest Song: In Critique of Solomon. Wipf & Stock Publishers.

Seerveld, C. (1972). For God’s Sake Run with Joy: Moments in a College Chapel.

Seerveld, C. (1980). Rainbows for the Fallen World: Aesthetic Life and Artistic Task. Tuppence Press.

Seerveld, C. (1987a). Imaginativity. Faith and Philosophy, 4(1), 43–58. https://doi.org/10.5840/faithphil1987411

Seerveld, C. (1987b). Temptation, Education, and Wisdom. Pro Rege, 15(3), 16–21.

Seerveld, C. (1988). On Being Human: Imaging God in the Modern World. Wipf & Stock Publishers.

Seerveld, C. (1991). Footprints in the Snow. Philosophia Reformata, 56(1), 1–34.

Seerveld, C. (1997). Take Hold of God and Pull. Authentic Media.

Seerveld, C. (2000a). Bearing Fresh Olive Leaves: Alternative Steps in Understanding Art. Toronto Tuppence Press.

Seerveld, C. (2000b). In the Fields of the Lord. Piquant.

Seerveld, C. (2001). Christian Aesthetic Bread for the World. Philosophia Reformata, 66(2), 155–177. https://doi.org/10.1163/22116117-90000229

Seerveld, C. (2002). Reformational Christian Philosophy and Christian College Education. Pro Rege, 30(3).

Seerveld, C. (2005a). Voicing God’s Psalms. Eerdmans.

Seerveld, C. (2005b, August 1). The Flash of a Fish Knife. Comment Magazine. https://comment.org/the-flash-of-a-fish-knife/

Seerveld, C. (2006, September 1). Making the Most of College: Philosophy as Schooled Memory. Comment Magazine. https://comment.org/making-the-most-of-college-philosophy-as-schooled-memory/

Seerveld, C. (2009a). A Response to Nathan Jacobs. Journal of Markets and Morality, 12(2).

Seerveld, C. (2009b, October 25). An Accidental Blog: Calvin Seerveld’s Writings 1995-2008. An Accidental Blog. http://stevebishop.blogspot.com/2009/10/calvin-seervelds-writings-1995-2008.html

Seerveld, C. (2012, November 14). The Theatre of God. Comment Magazine. https://comment.org/the-theatre-of-god/

Seerveld, C. (2013, March 1). The Pros of Christian Organizations. Comment Magazine. https://comment.org/the-pros-of-christian-organizations/

Seerveld, C. (2018). WANTED: Vegetarian Kuyperians with Artistic Underwear. Pro Rege, 46(3).

Seerveld, C. (2024). Tough Stuff from the Bible, Tendered Gently: Encouraging Faith Manifestoes for People with Open Ears: Biblical Narrative History. Cantaro Institute.

Seerveld, C. G. (1968). A Christian Critique of Art & Literature. Paideia Press.

Seerveld, C. G. (1985). Dooyeweerd’s Legacy for Aesthetics: Modal Law Theory. In The Legacy of Herman Dooyeweerd: Reflections on Critical Philosophy in the Christian Tradition (pp. 41–80). University Press of America.

Seerveld, C. G. (2003). How to Read the Bible to Hear God Speak: A Study in Numbers 22-24. Toronto Tuppence Press.

Seerveld, C. G. (2014a). Art History Revisited: Sundry Writings and Occasional Lectures (J. H. Kok, Ed.). Dordt College Press.

Seerveld, C. G. (2014b). Cultural Education and History Writing: Sundry Writings and Occasional Lectures (J. H. Kok, Ed.). Dordt College Press.

Seerveld, C. G. (2014c). Cultural Problems in Western Society: Sundry Writings and Occasional Lectures (J. H. Kok, Ed.). Dordt College Press.

Seerveld, C. G. (2014d). Normative Aesthetics: Sundry Writings and Occasional Lectures (J. H. Kok, Ed.). Dordt College Press.

Seerveld, C. G. (2014e). Redemptive Art in Society: Sundry Writings and Occasional Lectures (J. H. Kok, Ed.). Dordt College Press.

Seerveld, C. G. (2020). How to Read the Biblical Book of Proverbs: In Paragraphs (J. H. Kok, Ed.). Dordt College Press.

Seerveld, C. G. (2023). God Picks Up The Pieces. Dordt Press.

Zuidervaart, L., & Luttikhuizen, H. (Eds.). (1995). Pledges Of Jubilee Essays On Arts & Culture In Ho. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.

Peter, This is a masterful overview of Cal Seerveld’s life and person and work. What a tour de force you have crafted! And it is so very well written. I had no idea you knew him that well, forgetting the Willowdale connection that you had.

You have a great gift for doing these biographies. They all deserve wider dissemination. Maybe an e-book?? Keep up the good work, Justin

LikeLike

Thank you, Peter.

LikeLike